Jens Lekman

Casting his mind back over twenty years to his first rudimentary experiments with sampling using his father’s old cassette recorder, Jens Lekman recalls an instinct to create music that would set him far apart from his Swedish pop peers: “All my friends were playing in these bass-guitar-drum bands,” he says. “I’m going to sound like Scott Walker. But I’m going to do it in my bedroom.”

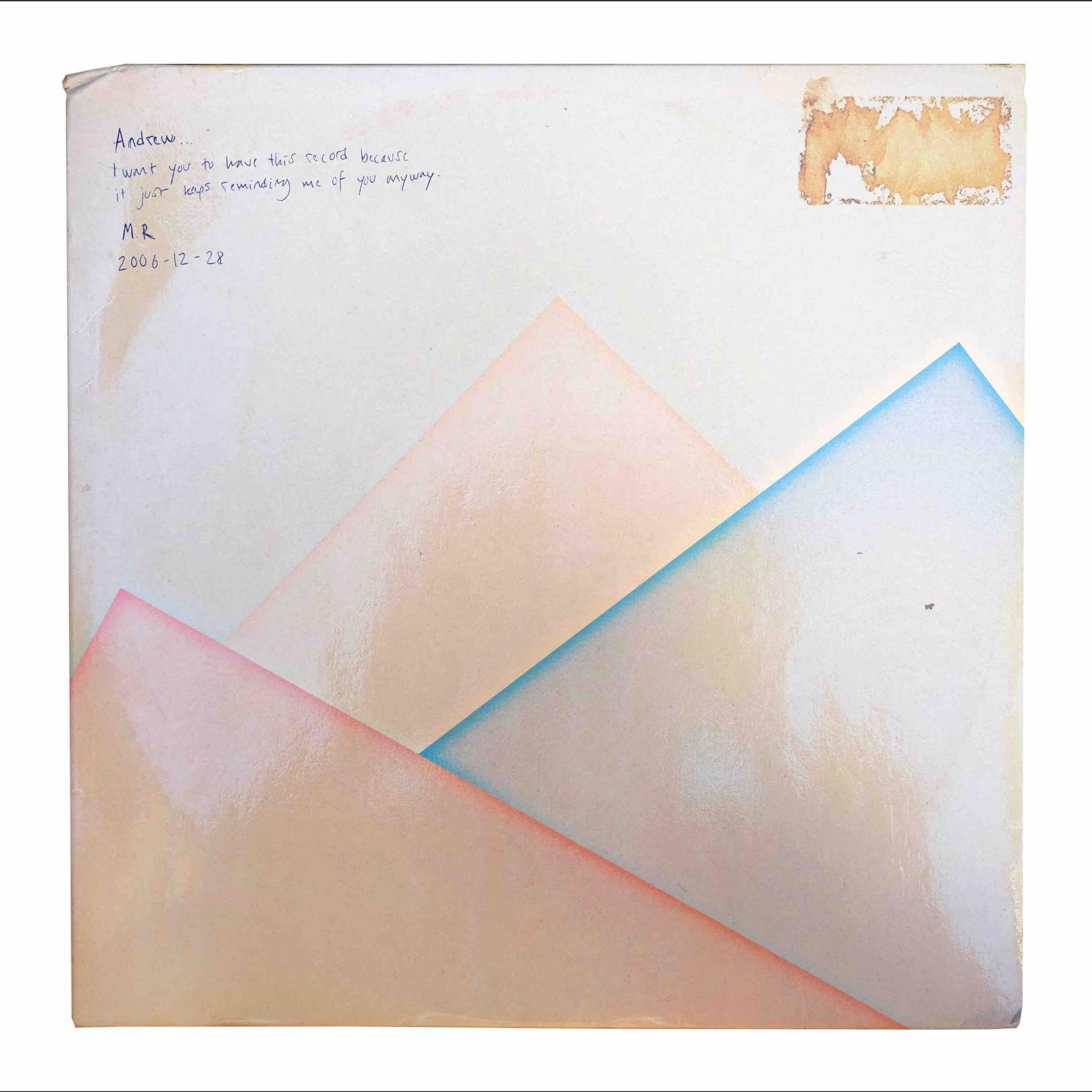

Works of sweeping, maximalist, orchestral wonder sung in a sumptuous tenor, weaving lifts from obscure flea market vinyl records, telling burningly romantic and mordantly funny true-life tales from the sleepy-shadowy suburbs of Gothenburg, Lekman’s early songs come from a different time and place: an era when the internet was young, limitless and disruptive, sample culture was turning music inside out, and anything felt possible.

After initially finding an audience through peer-to-peer file sharing sites, Lekman signed to Secretly Canadian Records in 2003, and went on to release a slew of cherished material, including three cult limited-edition EPs – Maple Leaves, Rocky Dennis and Julie – later collected on the 2005 compilation album Oh You’re So Silent Jens. His DIY fantasias found their fullest and most celebrated form in 2007 on his second proper album, the exquisite Night Falls Over Kortedala – Lekman’s self-professed “dream record.” It went to number one in Sweden and was later hailed as one of the 200 best albums of the 2000s by Pitchfork, as well as one of the top 100 albums of the 21st century so far by The Guardian.

Now, both Oh You’re So Silent Jens and Night Falls Over Kortedala no longer exist in their original forms.

Oh You’re So Silent Jens enigmatically disappeared in 2011; Night Falls Over Kortedala followed suit in early 2022. Lekman’s impulse for giving old music fresh life and context has led him to remake the records under new names, each delicately positioned in dialogue with the past – the same albums, just different. The Cherry Trees Are Still In Blossom and The Linden Trees Are Still In Blossom are a pair of lovingly and painstakingly assembled reduxes, each keeping the same core tracklisting, spirit and source material as the originals, but blending brand new versions of some tracks, in part or in whole, together with many tracks left largely as they were. Both records are fleshed out with rare, previously unreleased, and even previously unfinished old songs, as well as other contemporaneous material such as cassette diaries.

“In many ways the remaking of these records is so much in line with what I was doing at the time,” muses Lekman. “These records are a way of keeping music alive. It’s not preserving music; it’s allowing it to change. Preserved music is dead. I think that’s something that makes me sad about music these days, that it feels sometimes like it’s a big museum. Like butterflies dipped into chloroform pinned to the wall. This is music that is allowed to change. That is in the music’s nature.”

Lekman’s dialogue with his past takes on an almost literal form on The Cherry Trees, through cassette diaries unearthed from the archive, woven throughout the fabric of the record like a kind of commentary. A plaintive, dream-like piano ballad inspired by the almost “motherly” feeling Lekman had towards the neglected flea market records he used to sample from, the album’s opener “The Department of Forgotten Songs” can’t help but assume new resonance. “I really felt a lot for those old records,” Lekman recalls. “I think that’s what every musician wants – that the music will continue to live on.”

The truest test of the project came in re-recording one of his most treasured early singles “Maple Leaves,” a song directly inspired in its original form by The Avalanches’ “Since I Left You” (“a very emotional record for me”), now reimagined on The Cherry Trees as a tender ballad burnished with warm strings. The re-recording is heavily informed by Joni Mitchell’s intelligent and refined 2000 re-recording of her 1969 classic “Both Sides, Now.” “When she wrote that song in her twenties, I don’t think she actually had seen love from both sides,” says Lekman. “A lot of these songs, when I wrote them, I didn’t know anything about love.” Another of Lekman’s breakout singles re-grown from scratch is “Black Cab,” young Jens’s tragi-comic illegal taxi ride to oblivion after killing someone else’s party, faithfully resurrected in two versions that map its dual evolution live – one a handsomely melodic full band pop song, the other a gentle acoustic lullaby.

By singing about Kortedala in Night Falls… the way that Leonard Cohen sang about New York or Edith Piaf sang about Paris, Lekman somehow elevated the neighbourhood to a place of unlikely pop legend. “I always called it the Twin Peaks of Gothenburg,” he says of the unstarry residential district where he lived in the mid 2000s. “It felt like the kind of place where mysterious things happen.”

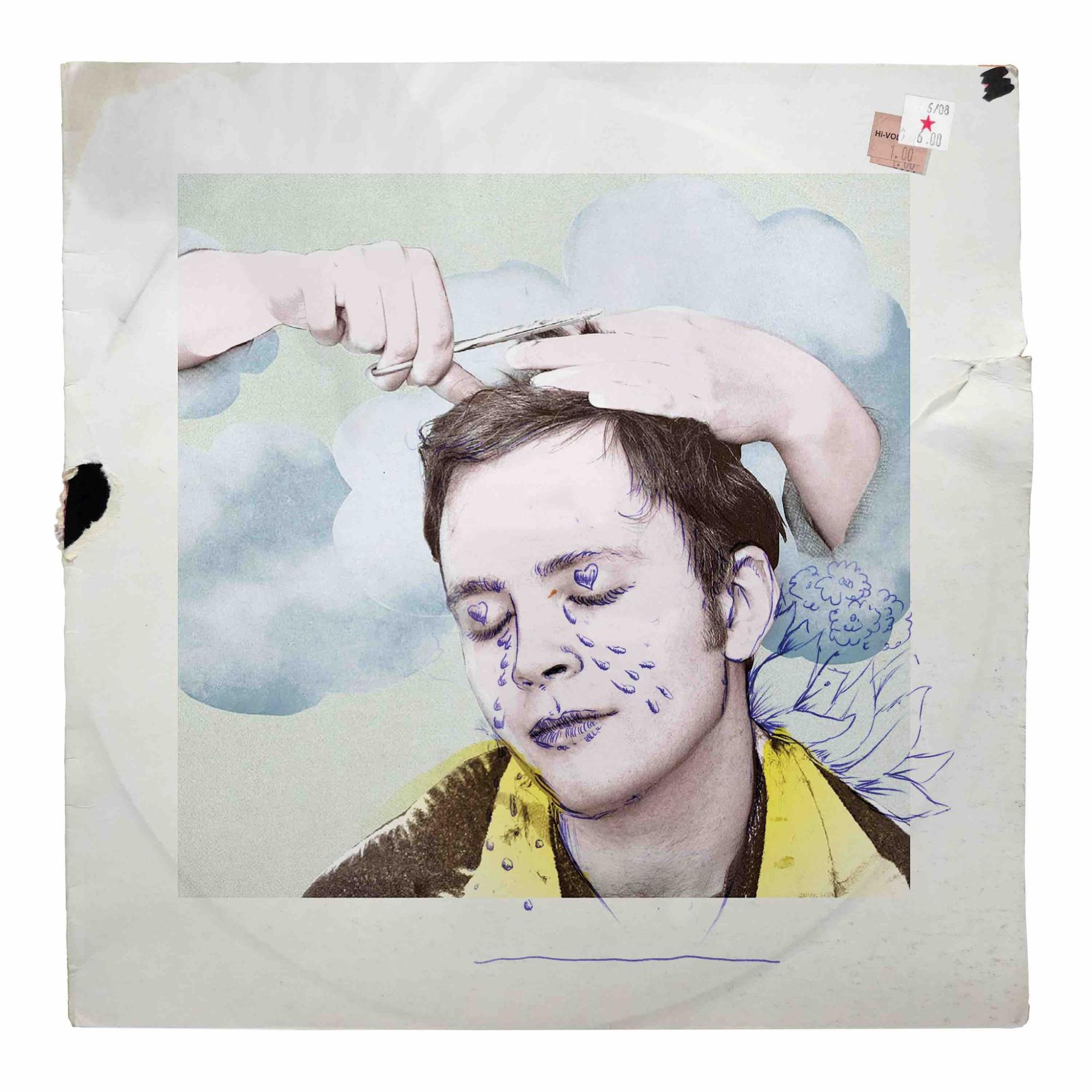

Stories and songs seemed to float into Lekman’s life as if already fully formed back then, and you can feel that magic still through The Linden Trees. “I remember as soon as I was on the bus home from Berlin I was like, ‘okay, this song is already finished,’” he remembers of “A Postcard to Nina” – a hilariously uplifting missive to a German friend who once duped Lekman into posing as her boyfriend to help conceal the fact that she was gay from her Catholic father. Similarly putting true life to stirring music is “Shirin,” the melancholic tale of how Jens used to get his haircut in an illegal beauty salon run by an Iraqi woman out of her apartment, as her mother sat nearby in a rocking chair. One day, without warning, they were gone. “I’m not even sure if her real name was Shirin.”

Elsewhere on the album, two of Lekman’s biggest hits live on in wholly familiar form: “The Opposite of Hallelujah,” Jens’s joyously tongue-tied attempt to dole out life advice to his younger sister, the track that launched a thousand air glockenspiel solos, and “Your Arms Around Me,” an open-hearted love song which, while not based in any real experience, has assumed significance through its reception by others. “Over the years just seeing people hug each other when they hear that song,” says Lekman, “having played it so many times at weddings, it has started to take on a new meaning for me.”

Following Night Falls Over Kortedala’s release, Lekman stopped working extensively with samples, subsequently taking a more traditional singer-songwriter approach on 2012’s I Know What Love Isn’t and 2017’s Life Will See You Now – albeit with that same crate-digging, collage-like feel now baked into his music. As such, The Cherry Trees Are Still In Blossom and The Linden Trees Are Still In Blossom together form a sort of belated farewell to Lekman’s formative days as a bedroom Scott Walker, panning for sample gold in stacks of vintage vinyl. Albeit not a farewell to the original albums themselves, which will live on in fans’ record collections, and perhaps illicit corners of the internet.

“I feel like these new records are like portals that can lead you to the old records if you want,” Lekman reflects. “I think that they can lead you to another time and a place, where you could work with music in a different way.”

Malcolm Jack